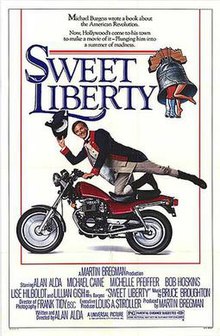

"There are only a couple of things I have a problem with--the story and the dialogue."

-- Michael Burgess (played by Alan Alda) in Sweet Liberty

What a difference a month makes.

The last time I posted here, I was struggling with the prospect of writing a

bad review. Now here I am, about to give one.

As a historical fiction writer and

a college professor who has slogged through the archives of Long

Island's Revolutionary War history for personal and professional

reasons, I had the highest hopes for AMC's Turn.

For too long, Long Island's history of British Occupation and the covert role

that Long Islanders played in helping our young country win the war has been

side-stepped by American history textbooks and teachers alike. Turn, I believed, would begin to educate

the public about what really happened on Long Island

during the American Revolution. Or so I'd hoped.

In the first episode of Turn,

Abraham

Woodhull is "turned" by childhood friend Benjamin Tallmadge against the

loyalist leanings of his family and the greater Setauket community. He

secretly pines for Anna Smith Strong, his ex-fiancé, who runs Strong

Tavern

in her arrested husband's absence (Selah Strong has been incarcerated

for accidentally

assaulting a British officer during a tavern brawl, leaving Anna to fend

for herself), and Woodhull convinces her to pitch in by hanging her

black petticoat on her clothesline as a signal when he has intelligence

to share. Woodhull then takes an oath of

loyalty to the crown in a Setauket public square to solidify his cover

before getting down to the business of surreptitiously changing

young America's fortune in

the War for American Independence.

This all sounds exciting and

fantastic. What it lacks is historical accuracy. First of all, Abraham Woodhull was not a Tory. He served on the

Committee of Public Safety in Brookhaven

Town, he was a lieutenant

in the local militia, and he signed an oath of loyalty to support the

Continental Congress prior to the occupation. When Tallmadge suggested spying for the cause,

Woodhull would have had no problem with the request. In fact, it might even have

been Woodhull's idea.

Second, Woodhull was 26 in 1776

and was single for the first five years of the war; he didn't marry Mary Smith

until 1781*, a time at which the British were beginning to redirect Long

Island-based troops to support to their flailing South Carolina campaign. Abraham and Mary

never had a son named Thomas, nor did Abraham have a predeceased brother by

that name who was held up as a shining example of who Abraham should be in order to please his

demanding father Richard.

|

| This romance never happened. |

Third, no engagement to Anna

Smith Strong ever existed, and no arranged marriage brokered by Woodhull's

father and Obadiah Smith ever thwarted his intentions to marry her. Anna (Nancy)

Smith married Selah Strong in 1760, when Woodhull was just ten years old, and she birthed her first child in 1761. By age 36

in 1776, she was pregnant with her seventh child, a boy born in December of

that year. Despite this large brood, "Annie" is portrayed as childless in Turn; the Strong children have been written out to smooth the way

for the imaginary romance. Yes, Selah Strong was arrested and sent to the

notorious prison ship Jersey, but for the crime of espionage. Strong didn't even own a tavern in Setauket; he was a farmer. The real Setauket tavern

owner in the spy ring was Captain Austin Roe, a patriot who for whatever reason

has yet to make an appearance in the series.

In summary, a sizeable chunk of

this true story has been completely fabricated.

My problem with Turn stems from this belief: Historical

fiction has an obligation at least to try

to get the facts right, and especially so when using the names of real historical

figures. Consider HBO's excellent John Adams series, based on David McCullough's masterful book. The scriptwriters

didn't have John Adams lusting after another woman, nor did they feign his

ideology or write in/out family members to match an altered story line. In John Adams, the historical record

remains largely intact. Imagined scenes, such as the conversation John holds

with cousin Sam Adams prior to a public tarring-and-feathering, are present

solely to develop characters further. There's no need to "sex up"

John Adams' story by adding fictional elements. It's "sexy" enough as

is.

The same truth holds for Long Island's history. After the American loss at the

Battle of Long Island, British soldiers subjected the island's inhabitants to

numerous documented abuses. Twenty two thousand British soldiers and Hessian

mercenaries were stationed there, matching the adult population in number. Martial

law was imposed. Ports were closed, and travel off Long

Island became impossible without British permission. Beatings,

robberies, rapes, murders and other crimes were committed by the British with

impunity. Although the island became a safe haven for Tory refugees, loyalists living

there still carried "papers of protection" in case they got into a

scrape with the soldiery. One can easily reason that it was a desperate time

for residents of colonial Long Island.

Yet these remarkable circumstances

somehow failed to create a compelling enough backdrop for Turn. Illicit romance and exaggerated loyalist sympathies are

introduced to make Abraham Woodhull not only a spy, but a married man living on

the edge, torn between his "true love" and his wife, always in danger

of being caught by a Tory neighbor. Apparently, the potential threat of torture

and execution upon discovery of his spy work wasn't considered enough to

keep the viewing public intrigued. The story needed additional fictional

elements to be made more appealing.

In 1986, Alan Alda starred in Sweet Liberty, a movie about a history

professor who watches in horror as the movie adaptation of his ancestor's

Revolutionary War diary deviates from the original true story to a fictional one of

illicit romance between his ancestor and a British officer. In the film, changes

are justified by movie-makers as a way to make history "more

interesting" for young people. The parallel between the plot of Sweet Liberty and what's happened in Turn causes more than a little déjà vu. [Watch the trailer here.]

Turn also engages in what I call McHistory--that is, the

oversimplification of complex historical situations so as to avoid any

bothersome critical thinking. The scholar-debunked idea that Long Island was

"mostly Tory" persists in character dialogue; the first episode emphasizes

in an almost cartoonish way that Whigs will find "no friends in New York." Richard

Woodhull, a judge, is portrayed as a staunch loyalist. Never mind that

this is the same man whose father's and grandfather's graves were

"desecrated" by British soldiers**--an act that Turn portrays as orchestrated

by said Woodhull on British behalf. Young Abraham "turning" against the

imagined Tory ideology of his community is far more dramatic than the reality:

The island contained a minority of die-hard loyalists in 1776 and was rabidly

patriotic by the end of the British occupation--a fact supported by the island-wide

"Tory purge" of 1783 in which loyalists were forced to flee by ship

to Nova Scotia immediately following the signing of the Treaty of Paris.

All of this goes to show that one

can't get his/her history from a television show. Despite the televised endorsements

of historical societies and "historians," Turn is not the true story of Long Island's

first spy ring. It's Long Island's very own

version of Sweet Liberty, brought to

life by attractive and talented actors (the only reason to watch) who likely have no idea that the

"history" they're portraying is more creative license than fact, the

product of a scriptwriting arrogance that oversimplifies and "improves"

real history for entertainment purposes.

I just hope that the people who

brought John Adams to life for HBO

will get around to making a true version of the Culper Spy Ring story someday. That

would be worth watching.

* Not 1784, as stated in The Woodhull Genealogy. See Records of the Town of Smithtown, by Wm. S. Pellatreau, pp. 476-477

** Per the notes of Morton Pennypacker, on file at the East Hampton Library's Long Island Collection.

** Per the notes of Morton Pennypacker, on file at the East Hampton Library's Long Island Collection.